The Old Swan Band ...a retrospective by Vic Smith

In the years either side of 1975, a revolution took place in English Social Dance. The dominant force throughout the 20th century had been the English Folk Dance and Song Society. There had been a previous major change in the first years after 1945 when the young royal princesses took an interest in square dancing after visiting Canada. The EFDSS heartily endorsed this and the bands that played for their ubiquitous dance clubs adopted many of their reels and played them at speed. Song tunes and tunes to hum along to – like Red River Valley – dominated their repertoire. In the mid-70s a new breed of bands and dancers swept in and they came from folk enthusiasts but not from the Society dance clubs. This movement seemed to emerge spontaneously all over the country with the main inspiration coming from three bands - in the north, The New Victory Band, in Gloucestershire, The Old Swan Band and a little later, Flowers & Frolics in London.

Surprisingly one of these bands is still in existence 45 years later and even more amazingly, three (or even four depending how you look at it) founder members still play with the band. The core of this article will be an interview with sisters Jo and Fi Fraser, who were in at the start even though they were just schoolgirls at the time. This will be augmented by comments from Paul Burgess and John Adams, but we should start with the person who came up with the idea in the first place, Rod Stradling.

Rod and Danny met and married in the mid-60s and were soon running a folk club together, initially at The Fighting Cocks in London and later, when they moved to Camden, another at The King’s Head in Islington. Both these clubs emphasised the importance of learning tunes and songs from traditional performers. By the time Tina and I met them – when they were putting up their tent next to ours at the TMSA festival campsite in Blairgowrie in 1969 – we found that there were a lot of parallels in what we were doing and we became friends. The Stradlings formed a band called Oak with Peta Webb and Tony Engle. This was short-lived; two or three years or so, but was very influential, making lots of appearances in London and the South-East including several for us in Lewes. They were learning their songs from the likes of Bob Hart and The Copper Family and their tunes from the likes of Scan Tester and Oscar Woods; people who they were able to meet in those years. When Bill Leader offered to make a record with them, Tony, who was already working for Topic Records, stepped in with a suggestion that the album should be on that label. Welcome To Our Fair helped to increase the impact of the group.

With a young son, Barnaby, a move away from the metropolis seemed to be the right choice for Rod and Danny, and they moved to Cricklade on the Wiltshire / Gloucestershire border. Rod soon made himself known to the Old Spot Morris. Paul Burgess, still a sixth-former at the time, remembers the impact of this down-from-London figure: “There was this bloke turned up in his smart shoes and Cuban heels, and it was Rod, and he was trying to get this stuff together, sorting things out to get a band.”

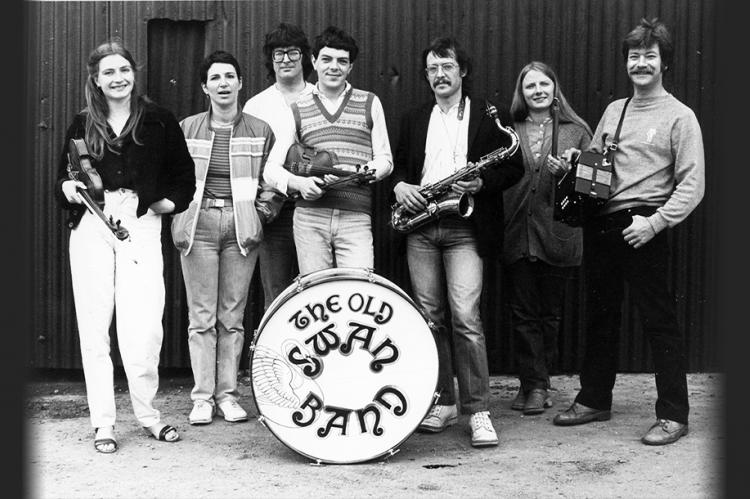

We’ll let Rod take up the story. “I had met Martin Brinsford through my involvement with the Old Spot and, when I moved from teaching to carpentry, we worked together, and he stayed at our house for a year or so. I encouraged him to learn mouth organ and melodeon. Danny, Martin and I then formed a backing band for the eccentric vocal talents of Ken Langsbury. However, the line-up was flexible (depending upon how many cars were available - so far, there was one car-full!). Another car meant more musicians. In 1974, this line-up, augmented by Old Swan pub session regulars Jo Fraser on whistle, Fi Fraser and Bernie Cherry on fiddles and Robin Lister on trumpet, meant two cars! We played at the Islington Folk Club under the name, The Cotswold Liberation Front. By the Sidmouth Festival of 1975, Robin and Bernie had left, Ron Field had joined on banjo and autoharp and the name had become The Old Swan Band. We soon realised that to work regularly we would have to play dances, not folk clubs, and it wasn't long before the band had a full diary and a record deal.”

Paul’s take on the name change was this: “I think we changed the Liberation Front name when all the IRA bombing was going on and it became a sort of unfortunate name.” The name was partly a joke, but behind it was the intention to reclaim a local traditional tune culture at a time when sessions were dominated by Irish music.

Having mentioned Fi and Jo, let’s introduce their contribution. The location of my interview with them about The Old Swan Band was far from salubrious - a store cupboard of a Lewes pub - but the conversation was fascinating. They had just finished an all-day harmony workshop as members of Narthen and were performing at the folk club in the evening. Interviewing siblings or parent and child often brings a sort of joint narration, and this was a classic example. Jo and Fi would finish off one another’s sentences, would augment or amplify what the other was saying, would pause and look at the other for confirmation - so to distinguish here what each one said would be pedantic in what is, after all, a joint story…

“The Cotswold Liberation Front was quite a big band. It was loosely arranged on two morris sides - Old Spot Morris and England’s Glory – and their musicians and singers. The first gig under that name was in December 1974 and was at the Campbells' club in Birmingham. The band carried on that name for a while and then it morphed into The Old Swan Band. We did mostly song gigs to start with, but we were playing the dance tunes as well and that's how the dance band came about. There was a session in the Old Swan pub in Cheltenham on Saturday lunchtimes which became a regular event. A lot of people knew about it and most of the people in the band went. More recently these sessions were on a Wednesday or Thursday night - and you have to bear in mind that at this stage we were 13 and 14 years old. We were given a pass-out by our mum to go to the session, but we had to be back by 10 o'clock. The Swan wasn't very far from our house and we were allowed to go one night a week. Local musicians in Gloucestershire had drifted away from playing English music and were playing predominately Irish music and a little bit of Scottish music. So this was part of the English Country Music Revival.”

The early line-up of the band was not settled, and there was a fair amount of coming and going. Paul became a part-time member for a few years whilst he was at college in London. Jo and Fi tried to remember other early members: “Ron Field had been playing banjo and autoharp with us, but then we gained a piano player, Richard Valentine, and that was very funny because we did three gigs before we thought of introducing him to the rest of the band! He was quite shy with us; he would just do the gig and then he would disappear, so it was about three weeks before we got around to introducing him… and he is such a lovely piano player. Who else? We had Robin Lister who played trumpet for a while; Mel Dean at one point who contributed trombone and percussion.” Later in my discussions, John Adams was able to add another name: Chris Bartram.

I mentioned the importance of the three bands in my first paragraph here. “That's right,” said Fi and Jo, “and if you think about those three bands, they were quite big bands, whilst a lot of the EFDSS bands playing then were trios or quartets. It wasn't about making the music sound exciting; it was functional, purely to get people walking through dances. We wanted to make it functional by playing tunes at a speed that would make walking uncomfortable, so that people would have to step it out. That was our emphasis; to make the dancers step-hop or skip or whatever the dance required, especially the hornpipes.”

“Looking back on it, it could be very hard for those who were not used to it to be asked to jump up and down; it was quite a young person's game to be able to do that. But what you needed to have, particularly in those early days, was a caller who understood what we were doing. In the early days we had a few mismatches where we were put together with unsuitable callers for our approach, so we started to insist that we could choose the callers who would work with us. That started with The Old Swan Band.”

So, who were the callers in the early days? Paul said he found Dave Hunt very conducive to the band. “He was great, just right for us. I remember working with another caller and he said that we were not playing the right tunes…” Jo and Fi agreed: “Well we ended up, pretty much, settling with Dave Hunt. We did some with the lovely Hugh Rippon and Wyn Shergold, a little old lady from Bampton - you have to bear in mind our ages and remember that anyone over 45 was a little old! And Ken Langsbury called dances, we worked with him sometimes. Roy Dommett was also a caller who we worked with. And John Kirkpatrick. All these things, and these people, were building momentum. And a lot of these people were connected to the Morris.”

“Mum was a single parent with two daughters, and she was very lucky to fall in with the Morris dancing world, which seemed to be very accepting of a single mum and two daughters. It was by learning to play Morris dance tunes that we ended up learning the instruments that we played. Fi learned a bit of violin at school but she ended up playing fiddle for dancing, and I (Jo) got a penny whistle because it was cheap, basically. That all had a knock-on effect because we weren't just playing Saturday sessions, we were going around with mum and playing at weekends, and dancing as well.”

Paul also makes the important point of how much the attitudes and approaches of the band and the two Morris sides were interlinked. “People were saying, ‘We've got our own tradition, why aren't we playing that.’ Robin Lister in the Old Spot Morris did a lot of work finding out what many of the old tunes from our area were. Bernie was the one who was keen on learning from the old traditional musicians; pointing out what had been played by local musicians. That had a terrific impact on everybody. Rod went up to Cecil Sharp House and listened to all the musicians recorded in the sound library - Scan Tester, Bob Cann, George Tremain - people we didn't have any other way of finding out about. We all got poor-quality cassette versions of these, seeing how much we could learn from them. That stuff by Scan Tester; we had never heard anything like that.”

Another important point Paul made was about developing a style of playing both for Morris and social dance. “With the Old Spot, it wasn't a matter of going to the 'Black Book' (and by this he means Lionel Bacon's comprehensive volume of Cotswold Morris dance notation and tunes). They were trying to go back to one village side, and the interviews and studies that were done. Bernie was particularly important in promoting this approach over quite a lot of sides. He certainly got me playing the fiddle for the Morris, and the way that he looked at the fiddle playing for the Morris was completely different. This was shortly before I went off to college where I was doing music, so it was a parallel thing; I was looking at the way they played stuff in the Renaissance, so trying to find out the way to play the fiddle in your local style needed a similar discipline. It was great.”

“…The band was playing for dances and annoying a lot of people used to the reels-based Brands Hatch style of the EFDSS-type bands. The band played slowly; you actually had to dance, for heaven's sake, and not just walk or run around the room. Any exhortations to speed up were waved aside. Slowly the point was driven home - you could, and should, dance to this music…”

And Rod… “The band was playing for dances and annoying a lot of people used to the reels-based Brands Hatch style of the EFDSS-type bands. The band played slowly; you actually had to dance, for heaven's sake, and not just walk or run around the room. Any exhortations to speed up were waved aside. Slowly the point was driven home - you could, and should, dance to this music. Then, of course, the rules were gradually relaxed. The point had been made.”

Paul takes up the point about the rhythm. “One thing that I noticed coming back to play in sessions and with the band in Cheltenham after playing in London was that slight delay on playing the first note. It was emphasised by the bass drum and especially the way Fi plays the fiddle; that was a huge influence on me. The way you sink the bow into the strings and that is the thing that gives the tune a push rather than playing exactly on the beat which seems to kill it.” I think that the best example of what he is talking about are the two Walter Bulwer polkas; the opening track on their iconic first album, No Reels. Rod considers that “the band was dragged, rather reluctantly, into the recording studio… thinking of themselves as a live dance band.”

But the impact of this album in 1976 was huge and Fi does not seem to agree with Rod’s assessment. “Martin Brinsford and I had been asked by John Kirkpatrick to play on Plain Capers (also 1976) which was the very first album that I played on. What Plain Capers was trying to do was very specific. It was different from Morris On (1972) and it tried to show Morris tunes in a completely different light. Then, to go into the studio again with the OSB, I was just excited, so there was no reluctance on my part.” To which Jo adds, “I am not quite sure what Rod is getting at when he says that. Perhaps he was just thinking that there wasn't a market for it. As it was, we recorded the whole thing in a weekend.” They both continue: “It was on Free Reed, with Neil Wayne, and there wasn't a whole lot of money. We rehearsed it very well, knew exactly how many times we were going to play things and how the changes would be. It was all done before we got into the studio. Literally, we could all just walk into the studio, sit down and play.”

The band soon realised the impact the album had, as Jo relates: “It's worth mentioning that when we started appearing at a lot of festivals, after No Reels came out, we saw the influence of our band. When we arrived at these events, we were often asked to join in or lead sessions, and that was when you realised what an effect you had, because people would play these sets of tunes in exactly the order we played them - even if we played the 'A's and 'B's backwards, changing in the same place. It was amazing to think, ‘Oh my gosh! They are all playing exactly what we did on that album.’ It was that important to them.”

Two other albums followed, also on Free Reed - Old Swan Brand in 1979 and Gamesters, Pickpockets And Harlots two years later - and again the focus was on locally sourced dance tunes, but the former had five songs sung by various band members and the latter had two stories told by Ken Langsbury in his idiosyncratic style. Their popularity as a festival dance band continued, but a really significant change was on its way in 1982. Jo and Fi take up the tale.

“The band nearly folded. We were in the middle of a tour and Rod and Danny said that they wanted to leave the band. We were very upset about it, and afterwards we decided to meet all the rest of them, and though the line-up had changed, we decided to keep the name of the band… and a lot of the tunes actually, and a lot of the feel, but it just went in a different direction. Rod's playing had a unique stamp, but then we started to think about trying things in a different way.”

But how was this to happen? No-one seems to be really sure whose idea it was, but Paul says: “After Rod left, we all said, ‘Who do we get to play melodeon?’ Then we thought, ‘There are not so many people that we would like to get...’ They were either in other bands or we didn't think their playing would fit. So there was no point. I was guesting playing with another local band and they had Flos (Philip Headford) in their line-up. I mentioned enjoying playing with Flos, and someone said, ‘How about a three fiddle line-up?’ And that's what we did.”

Over to Fi. “Yes, we ended up with three fiddle players who melded together in a rather peculiar way; there were three very different styles, but when we put them all together, we ended up with this massive noise. It was wonderful.”

It seems to have come together organically, without any compromise. Paul explains: “That was one of the things we quite liked about it - that it wasn't smooth and beautifully worked out harmonies; with us it was a bit rougher. Fi might be playing the tune beautifully, the way she really sinks in the bow and drives the tune forward, me playing the tune with a bit of harmony and Flos… well… we never knew quite what he was going to do, but the combination was quite inspiring. It keeps you on your toes when you are never sure what is going to happen.”

The way the three tried to share what they did brought this memory from Jo. “I can remember a hysterical fiddle workshop that the three of them ran at Whitby. None of them actually played the tune entirely, but somehow it was always there when the three of them played; between them it was all implied. The three of them played this homogenous thing that the rest of us could add to, but these three became the meat of the band. It was fabulous.”

All this coincided with the arrival of John Adams. He says: “Of all the bands I’ve ever worked in, this is probably the most comfortable! Three top English fiddlers, backed by solid keys and one of the best percussionists around – augmented by three brass, of which I am one, joining after the demise of The New Victory Band. Richard Valentine moved off the piano stool in favour of Heather Horsley and one of my students at Salford, Neil Gledhill, was press-ganged into the band playing the rarely heard bass sax. Somewhere in the middle of these changes, a version of the band made an EP record (1983) and that was the last studio recording until the 2004 album, Swan-Upmanship.”

Brass had always been a part of the OSB. Mel Dean played trombone in some of the early line-ups and multi-instrumentalist, Martin Brinsford, played sax at times. Jo added the saxophone to her whistle playing. She says: “It wasn't until later on that I really took off on the saxophone, after I joined Blowzabella. The Old Swans bought me my first one, a C-melody, and I was playing relatively simpler lines to fill out with the bass end with the piano. When I joined Blowzabella in 1986, I went on to tenor sax and I became a much more fluid player because I was being challenged all the time, and that inevitably crosses over into playing with other bands. I was becoming more adept at playing tunes and harmonies, as I had been on the whistle, so I was developing musically as a person.”

“…they draw material from Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Quebec, as well as the more obvious USA, Australia, Scotland, Ireland and even England! It all goes into the Old Swan mincer and comes out as the most exciting English dance music that you are ever likely to hear or dance to…”

Swan-Upmanship was the band’s first album for Doug Bailey’s WildGoose label and three others have been Swan For The Money (2011), Fortyssimo (2014) and now Fortyfived. These years have seen a much more stable line-up with mature musicians, but the contagious danceability of their band sound has never flagged. One change that has occurred is their attitude to sourcing material. This is part of what I wrote in a review on their new album for Around Kent Folk magazine:

“This time they draw material from Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Quebec, as well as the more obvious USA, Australia, Scotland, Ireland and even England! It all goes into the Old Swan mincer and comes out as the most exciting English dance music that you are ever likely to hear or dance to… but a personal favourite would be what they have done to Alistair Anderson's Road To The North. This is normally heard as a thoughtful, almost sensuous melody on his Steel Skies suite. Here it is a really sprightly polka.”

I asked the sisters if this was fair, and Fi laughed. “Well, to be fair, I don't think that I had actually heard that tune! Nobody told me the way it had been played; I was trying to come to grips with the tune from the dots and get a feel for it, and Paul standing with me just went with me!” Then Jo added, “But that is exactly the point of that album. Fi and I have done a lot of workshops together over the years where we talk to people about the way we play rather than what we play. That's what that album is all about. It doesn't matter where the tune comes from, but if you want it to sound right for your band or for the English style, then it's about the way that you deliver it and the way that you feel and have empathy for it. You change it to the manner that suits.”

We talked about the aging of the band and of the dancers, but agreed that there was room for optimism. Yes, the dancers who were the wild enthusiasts for the band in the 1970s are dropping off from being regular dancers now. Then there is a generation, now in their forties, that seem to have missed out on folk dance, but there is plenty of evidence of young dancers discovering what their parents missed out on.

As for the future of the band, I’ll leave the last words to Fi and Jo, as usual providing overlapping statements: “We are talking about bringing in some younger blood to regenerate the band, so that as people retire others come in and we morph into something else… but hopefully with that same joyous, delightful party feeling to the music, music that is just such a joy to be part of.”

Photo: Ian Anderson

Published in Issue 135 of The Living Tradition - August 2020.